As a journalist who loves narrative nonfiction, I always read books written by journalists with questions about the processing of writing the book: How did they verify that detail? How did they pick the narrative? What challenges did they have getting people to share their stories?

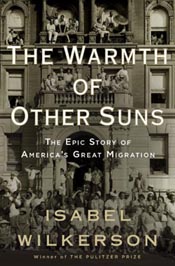

So when Isabel Wilkerson, author of the Indie Lit Awards Non-Fiction winning book The Warmth of Other Suns (which is a great book!) agreed to answer some questions, I was thrilled. Isabel graciously sent some amazing answers to my questions from the airport in Celeveland where she was stranded because of a blizzard — we have those often in the Midwest — after being on the road for two weeks talking about the book. I’m really honored she’d take the time to do that, and excited to share her responses with you. Enjoy!

Kim: What was your inspiration for trying to tell the story of the Great Migration?

Isabel: My inspiration for trying to tell the story of the Great Migration came from many places, expected and not so expected. In a way, it came down to connecting the dots from multiple sources of inspiration.

For one, I’m a product of the very phenomenon I chose to write about, and I owe my very existence to it. But that alone would not be sufficient reason because it’s the story of a great many Americans.

Several things happened to spark something inside of me. One was traveling as a national correspondent and bureau chief for The New York Times. It seemed that no matter which northern or western city I happened to be in, if I were interviewing African-Americans, they would invariably make a reference to a specific state in the South that they or their families had come from. The different streams and tributaries of this great movement were visible in most every interaction, and I began to realize that it had been a national outpouring of people over many decades. It made me realize how massive it was.

But probably what contributed most to my decision to devote myself to this book was a series of works on the immigrant experience that I so identified with, that spoke to my own childhood and made me realize that I had, in fact, grown up the daughter of immigrants, so to speak.

I saw myself in the daughters of Amy Tan’s The Joy Luck Club, daughters negotiating two forces — both the expectations of ambitious mothers who had sacrificed everything to come to a foreign land, and the New World that seemed at odds with the values of the Old Country. It occurred to me that, in the elite public schools my mother enrolled me in, I had gravitated to the children of recent immigrants because we had so much in common.

Another inspiration was the Barry Levinson film, Avalon, that described an immigrant family’s adjustment to the New World of Baltimore. When I saw it, I thought to myself that if you changed the names and place of origin, the film could have been about families that I grew up around in Washington, D.C., but who had migrated from Georgia and the Carolinas instead of eastern Europe.

I re-read The Grapes of Wrath with new eyes and realized there had been no The Grapes of Wrath for the Great Migration, and thought there ought to be something that would capture the hopes and dreams and journeys of these people before it was too late. I am not suggesting that this is equivalent to The Grapes of Wrath, but that I had it in the back of my mind as I set out to interview as many people as I could, reluctant though most of them were.

Kim: How did you decide on the title of the book?

Kim: How did you decide on the title of the book?

Isabel: At one point in the research process, I was reading a book a day — books on citrus production or southern geology or obscure court cases in Florida. I took to paying close attention to the footnotes and actually enjoyed reading them. I was reading the footnotes of the annotated version of Richard Wright’s autobiography, Black Boy, when I saw a passage that had been in the original published version of the book but omitted in the text of the current version.

This passage had not been part of the original manuscript he had submitted, and he had had to write it in haste when he had been asked to cut the second half of the manuscript in order to get it published. Under deadline, he had to find the words to conclude his now truncated autobiography, and those words were succinct and beautiful:

I was flinging myself into the unknown, I was taking a part of myself to plant in alien soil…to see if it could grow differently…. If it could drink of new and cool rains, bend in strange winds, respond to the warmth of other suns and perhaps to bloom.

I came across this passage fairly late in the writing process. Until I saw that footnote, I had neither an epigraph nor a title. That passage gave me both.

Kim: When during the research/writing process did you decide to focus on Ida Mae Brandon Gladney, George Swanson Starling, and Joseph Pershing Foster? Why did you pick them?

Isabel: I spent about a year and a half interviewing more than 1,200 people across the country who had been part of the Great Migration. I went to senior centers, pensioners’ unions, quilting clubs, AARP meetings, Catholic churches in Los Angeles where everyone was from Louisiana, Baptist churches in New York where everyone was from South Carolina and the different southern state clubs in northern and western cities, like the Lake Charles, Louisiana, Club in Los Angeles and the Greenwood, Mississippi, Club in Chicago.

It was like an audition in a way for the people who would become the three main protagonists. I was looking for three people to stand in for the six million who participated in the migration. I needed a person to represent each of the three migration streams and who left in a different decade, for different reasons under different circumstances, headed for different receiving stations and experiencing different outcomes. Which is why I took so much time interviewing so many people to find these three.

This was a generation that was often loathe to talk about the past — it was too painful. Many had not told their own children and grandchildren what they had been through. But I needed people who would be willing to share their experiences and be as candid about their failures and missteps as their triumphs.

I narrowed the 1,200 to 30 people, any one of whom could have been main protagonists and some of whom make cameo appearances in the book. I chose these three because together they tell a full story of the migration across geography, decades, class, motivation and outcome.

They were characters unto themselves who were ordinary people in extraordinary circumstances, and each could have been a book on his or her own.

Over time, I developed an abiding connection with them and them to me, which made the work all the more fulfilling. I’ve talked quite a bit over the last few months about how I chose them, but a Catholic priest in Illinois, who is a fan and close reader of the book, recently told me that he believes that they, in fact, chose me. They didn’t have to share their heartaches and life stories, and hadn’t even told their own children things they shared for this book. But they chose to do so when I appeared in their lives. And their decision was a gift to anyone who reads the book.

Kim: What was your favorite moment from the process of writing the book?

Isabel: I decided to do this book in two phases. The first was finding and interviewing the people who had lived this and who were all getting up in age; I was in a race against time to hear as many stories as I could before it was too late. The second phase required combing the archives for newspaper stories, old journal articles, long out-of-print books, obscure government reports, railroad maps from the 1930’s and other material that would put their experiences in context and provide as much detail as possible to make this time in American history come alive for the reader.

So during the writing, the most exciting moments were the discovery or arrival of an old document from the era. I spent a lot of time in library archives and found a lot of things on eBay. I needed to be able to describe Dr. Foster’s Buick Roadmaster, for instance, and, on eBay, I found an advertisement for the car from an old Life magazine with pictures and specs. He himself might have looked at that very advertisement as he dreamed of the car that would carry him to California. I found old train schedules on eBay and route maps for the Illinois Central Railroad from 1937 when Ida Mae Gladney left Mississippi. On eBay, I bought a Green Book, the now legendary guidebooks to safe lodging that black travelers relied on during segregation.

But a moment that stands out for me was when I got a hold of a copy of the original 1885 paper that had been delivered by a British historian before the Royal Historical Society in which the historian, E.G. Ravenstein, sets out the enduring motivations and behavior patterns of anyone who migrates. His findings have stood the test of time, and help explain so much about the Great Migration from the universally human perspective with which I approached the work. I had seen many references to what he called “The Laws of Migration,” but wanted to see his findings unfiltered, undistilled. I just remember that moment so well because I felt I was connecting across centuries with a kindred spirit who had devoted his energy to understanding this basic human need to find something better even if it meant going far away.

Kim: If there is one message you hope readers will take from the book, what is it?

Isabel: I would hope that people would come away from the book with a greater understanding of the lengths to which millions of Americans had to go to find freedom within the borders of their own country, to realize that it was not so very long ago that parts of our country were so totalitarian as to be more like the Soviet Union during the Cold War, and that this migration changed the country north and south and helped shape American culture as we know it.

Above all, I hope that people gain a greater appreciation for the sacrifices that someone in all of our lineages made for us to be where we are, and that, regardless of our backgrounds, we all have more in common than we’ve been led to believe.

Thanks again to Isabel Wilkerson for taking the time to answer some questions about her book, The Warmth of Other Suns! You can read this interview over at the Indie Lit Awards website, and check out my personal review of the book here.

Comments on this entry are closed.

This sounds like such an interesting book. Another one for the wish list!

Trisha: It’s a great book, I hope you get a chance to read it!

What a wonderful interview! I’m so glad you were able to interview Wilkerson. The Warmth of Other Suns is such an important book and I hope more people read it.

Vasilly: I’m glad I was able to interview her as well. It was fun!

Great interview! Thank you. Our interracial book club declared this one of the best books we’ve read. We’ve been reading and meeting for over three years, so that’s a lot of books we were comparing. We really want to see more members of our community reading it and have been talking it up around town.

Joy: Wow, that’s great! And it’s very cool you have been meeting for so long — I’m sure it’s an excellent book club. I hope more people will read this book, too.

I was already interested in reading this book, but the interview cements my interest. I loved how the author describes the thrill of discovery as she was conducting research for Warmth of Other Suns.

Christy: Me too! I think that’s one of my favorite things to learn, how exciting research can be.