And finally, the last two books that were part of the nonfiction list for the Indie Lit Awards this year! These last two books — Lost in Shangri-La by Mitchell Zuckhoff and In the Garden of Beasts by Eric Larson — were rereads for me. Rather than write two new reviews, I thought I’d link back to my original thoughts and share some impressions I had of the books in the process of reading and thinking about them again.

And if you’re interested in the other books that were shortlusted the year, check out my posts from earlier in the week.

Lost in Shangri-La by Mitchell Zuckhoff

Title: Lost in Shangri-La: A True Story of Survival, Adventure, and the Most Incredible Rescue Mission of World War II

Title: Lost in Shangri-La: A True Story of Survival, Adventure, and the Most Incredible Rescue Mission of World War II

Author: Mitchell Zuckoff

Genre: Narrative Nonfiction

Year: 2011

Some Thoughts From My First Read: Lost in Shangri-La perfectly exemplifies everything that I love about narrative nonfiction. It puts a new twist on a familiar story, shows meticulous research through primary and secondary sources, and pulls these pieces together with well-spun characters and a story full of the dramatic ups and downs of the best adventure fiction. …

The way Zuckoff wrote about the survivors and rescuers was amazing. In just a few pages I was emotionally wrapped up in their stories, worried about them as they boarded the plane and mourning with them as they lost close friends in the crash. It’s just a great story and I highly recommend the book, especially for people looking for accessible and entertaining nonfiction — you won’t be disappointed.

Thoughts on a Re-Read: One of the big discussions the panelists had as we tried to pick a winner was about the scope of nonfiction — does a great book need to take on a big event, or can we be equally as enthralled with a compact, self-sustaining story?

Of all the books we considered, Lost in Shangri-La has the most limited scope, focusing on just a single plane crash and the aftermath. In some ways, that makes the stakes lower — fewer people are impacted by the outcome. But in other ways, Lost in Shangri-La captures the human drama of disaster and tragedy better because of it’s tight focus on this particular story.

Although I loved almost all of the books that made the short list, Lost in Shangri-La was my favorite (by just a tiny, tiny bit). The story Zuckhoff tells probably lost a little bit of the emotional punch on a second read, but otherwise it was just as great a second time around.

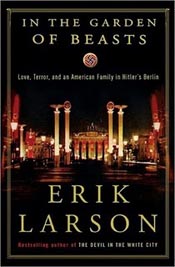

In the Garden of Beasts by Eric Larson

Title: In the Garden of Beasts: Love, Terror, and an American Family in Hitler’s Berlin

Title: In the Garden of Beasts: Love, Terror, and an American Family in Hitler’s Berlin

Author: Erik Larson

Genre: Narrative nonfiction

Year: 2011

Acquired: From the publisher for review/at BEA

Some Thoughts From My First Read: By putting this father and daughter next to each other, Larson is able to show the range of attitudes about Hitler’s rise to power — veiled caution to complete disregard — and how those attitudes came about. There’s no real blame to be placed on any one person or even group of people for letting Germany derail so completely, and I felt like Larson was able to make that case through the book.

The only other Larson book I’ve read is Devil in the White City, which was about the the 1893 World’s Fair in Chicago and a serial killer in the city. Ultimately, I think In the Garden of Beasts might be a better book — the narrative feels like it has more of a cohesion to it. There aren’t as many moments of obvious violence, but the tension Larson builds through the small acts of terror he writes about build to a terrifying conclusion.

Thoughts on a Re-Read: There is so much to admire about the way In the Garden of Beasts is crafted. Larson’s choice to write about both James Dodd, the ambassador, and Martha, his daughter, gives the book so much depth and way to write about both politics and personality in Hitler’s Germany without one feeling forced. They’re such good foils too each other, but I think it takes a master of narrative nonfiction to see that and write about it so well.

I will say that on a second read some of Larson’s writing quirks stood out to me since I knew what to expect from the plot. He has a tendency to, for example, foreshadow an event that’s either too vague or too far in the future to have an impact. You get all these moments of, “Ooo, something terrible is going to happen!” that don’t payoff quickly or obviously enough. But I think that’s a pretty specific and minor quibble for a book that’s otherwise absolutely excellent.